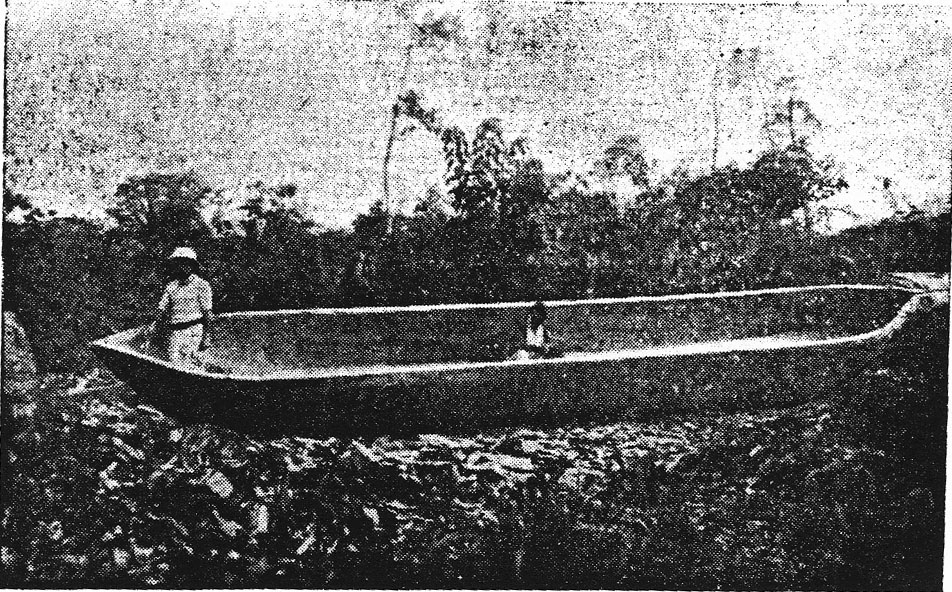

Building a cayuco, or dugout canoe, circa 1930. (Photo from Los Bubis on Fernando Poo)

Chapters 1 to 4: Earliest Bubis

1: Bubi emigration

That the indigenous people of Fernando Poo Island belong to the large Bantu family is fundamental knowledge for anyone hoping to become even moderately educated in African ethnography and ethnology.

In the opinion of celebrated Africanist Delafoss (1) and others, the original Bantu were from numerous villages situated south of an irregular demarcation line that divides Rodolfo Lake, ends in the mouth of the King River in the Atlantic, runs from here to the Cape of Good Hope, and only among them exist ethnic and linguistic ties.

The Bantu never formed vast states or huge empires in the manner of the strong Sudanese family. Not that the Bantus were in any way inferior to the other African races, from the social and political points of view, nor in them was there less passion for profit, ambition, power, and authority – traits that produced conquerors and founders of expanding empires. It is simply that their country is covered in large part by dense and impenetrable jungles and crossed by innumerable waterways. Annual floods present insurmountable obstacles and, therefore, make the area less favorable for military enterprises, political relations, and trade.

Bantu origin is much obscured, and at the present it is a little less than impossible to mark for certain their ancient region. Nonetheless, the majority of anthropologists who have thoroughly studied the subject agree that the Bantu cradle was an immense territory of lakes between the source of the Nile, Congo, and Ubangi rivers.

Africanists disagree in which era the dispersion of different Bantu groups took place. Some are of the opinion that it was around the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, each group taking a different direction, and it can be affirmed with enough probability that the Bubis were the first to abandon their country of origin. The proof of this is that their tongues correspond to the first formation of the Bantu language, according to the common belief of the Africanist philologists. (2)

2. Arrival of the Bubis on Fernando Poo

Having headed northeast, and thus favored by the current, they landed, almost all, on the beaches between Point Santiago and Conception Bay. The Biabba tribe arrived at the mouth of the Ilachi River and from here, following both banks, they ascended to a high plateau. In this same place where they rested they established their base.

The Baloketo, Basakato, Baney, Basuala, Baho, Bakake, and Bariaobe disembarked in Conception Bay. The Baloketo, the most numerous and powerful tribe, took possession of the hill that divides the island in two big pieces, that which separates the bays of Conception and San Carlos. It is here that the island divides east and west. For the part east that was situated north of the Baloketo, the Baho, Bakake, and Bariaobe tribes settled; and the Basakato, Baney and Basuala made their homes on the west side. Many families of the Bakake, who are today the Urekanos, and the Babiaoma, the Balacha of San Carlos, and the original Batete, reached port to the west of Point Santiago. They gave it the name of Mahala moe nebila, this is, “Point of the Palm Trees.”

The Bareka secured their residence on the island’s southern beaches, dividing into five big villages. The Balacha, Babiaoma, or people of Ombori, the Balombe and original Batete took Balacha pass, which is formed by the Malaoko mountains to the east, and the Lopelo mountains to the west, and gives easy access to Ureka from San Carlos Bay. They built their homes on the slopes north of the aforementioned mountains, forming the districts of Ombori, Balachalacha, and Batete. It has been indicated that in their land of origin the Bakake and Bareka formed a family or Bubi subtribe. The proof is that both villages have an identical language, distinct from the rest of the island’s regions and towns. The unique difference between both languages is that the dialect of the Bareka abounds with the voices of Riaba, Ombori, and Batete, and it agrees with southern area in its grammatical rules and word formation, while the Bakake follow those of the northern area. That difference comes from long and continued dealings and communication with the neighboring villages.

3. New Immigration on the Island

The last Bubis to land on Fernandian beaches were today’s Batetes and Bokokos, who waylaid on southern shores where the Bareka had already taken up residence. The mochuku or chief of the Bareka, in observing the enormous crowd approaching his country, feared he was under attack. He cried out: “The earth that I walk on is mine; no one can dispute that. I am ready and able to defend it with my blood and with that of my subjects.” The Urekanos shouted their approval to their chief with a tumultuous Ucce! (“Hurrah!”)

The newest arrivals told the chief, named Moaeddo, that they had no evil intentions. They had come to the island to make their homes on new lands, not on those already inhabited. Moaeddo considered this, then permitted them temporary residence. The mochuku of the Bokokos, who guided that vast caravan of Bokokos and Batetes, responded to Moaeddo’s benevolence with courteous thanks, promising, in turn, to cause no him bother at all. More, he said, the stay of the Bokokos and Batetes in Ureka would not be long.

Then a disgraceful, defamatory incident brought trouble to those beaches.

The Bubis, before leaving the continental coast, would supply themselves with full loads of seeds from yams, malangas, and other edible plants. It happened that the Batetes forgot to bring seeds for a yam most esteemed by them, called rea. They asked a motete (captain) to acquire some, but it seemed to him impossible to get any through legitimate means. So he stole some from Moaeddo.

Moaeddo quickly knew about the theft and the criminal’s identity. He called for the mochuku of the Bokokos and Batetes, though in that time the Batete lacked their own chief. Moaeddo, infuriated by such a reprehensible deed, reprimanded the Bokoko chief, condemning him, his undisciplined subjects, and their terrible customs. He ordered their chief to take his people and leave. He no longer wanted evil, thieving tribes for neighbors.

Among the early Bubi, the most serious and defamatory crimes were robbery, theft, and adultery. Therefore, the chief of the Bokokos and Batetes had no words to respond to the just recriminations of Ureka’s chief, having seen for himself the offense perpetrated by one of his subjects. He knew Moaeddo used his legitimate right to expel them. The mochuku called together his subjects, told them about Moaeddo’s expulsion decree for the motete’s crime, and in that magnanimous assembly ordered the thief’s right hand cut off, according to Bubi law and custom.

From this act, we have the origin of the old antagonisms and perpetual quarrels that exist even today between the Batetes and Bokokos.

4. Into Exile

The sentence decreed by Moaeddo was carried out to the letter. The Batetes and Bokokos gathered up their meager furnishings and supplies, immediately setting off on the march.

The chief divided the people into three large bodies, putting at the vanguard and rear guard the robust men and those carrying arms. The central body comprised the chief’s principals, elderly persons, women, and children. But when he gave his order for the male Batetes to go up front, they refused. The Batetes were always insubordinate and independent. The chief, faced now with a potential crisis and trying to avoid worse disorder, held his temper and complied with the Batetes’ wishes, deferring punishment for their rebellion until later. They moved to the rear guard and the Bokokos to the vanguard. Here was another cause for the rancor and resentment of the two regions.

The Bokokos in that time were larger in number than the Batetes. They had brought from their native land a huge drum and an enormous cooking kettle, which they had given the name Mocaponda. The Batetes brought a canoe in miniature called Lobende, which served as a memorial to the prosperous navigation and happy arrival in their own homeland. They preserved it as a sacred thing; its guard and conservation entrusted to one of the women of highest Bubi nobility. They brought it out from time to time to celebrate the most solemn festivals thanking their ancestors for bringing them to a country so rich and fertile. In the festival of Buala, which was most important among them, an armed body of the respective district escorted Lobende. It was of such solemnity that no one profane was allowed to see it, and even in the main festival they carried it veiled and covered with leaves.

I have assisted in these solemnities, seen this same Lobende, witnessed the ceremony with which it is carried, and I am familiar with the hut where they guard it.

The Bokokos and Batetes, in leaving Ureka, headed in a westerly direction, going along the beaches to the south to a point near the mouth of the Ole River, named Ncholó. Soon it became night, but so dark and pitch-black that, as they tell it, never had there been such a night.

In spite of this darkness, and without carrying mapaho or torches, they marched on, a costly imprudence. The old ones recount that the vanguard arrived at Ncholó, which was a large, deep marsh, and believing it to be a simple pond, pressed forward. They rushed headlong, a large part of the vanguard drowning and the drum bearer perishing as well.

After a time, when the chief could no longer hear the drum’s rhythmic sounds, he feared some misfortune had occurred and that the caravan was in grave danger. He ordered them all to stop, demanding that no one take another step. They remained in this way until dawn, frozen, fearfully contemplating the fate of the vanguard.

This fatal event provoked a terrible fight between the Bokokos and Batetes. The Bokokos blamed the Batetes’ tenacious refusal to go to the front for the death and disappearance of their brothers. Nevertheless, the prudence of the mochuku and the fear the Bokokos had of the Batetes kept the fight from escalating.

From this night, we have the separation of the Batetes and Bokokos. The Bokokos finally threw off Batete domination, naming a motete to direct and govern them. To this day, when two close friends break their friendship they use the proverb: Be achoanera Ncholómba, “They separated in the Ncholó marsh.”

The Bokokos continued their march along the beach, fording the Ole, or Tudela, and camping between the Itepo and Okó rivers. The Batetes wound to the right, moving inland by the Ole to the Grand Caldera of Batete, which is an extremely deep and immense valley formed by the mountains Lopeló, Sosó, and the Urekanos. The Batetes lived in these depths for many years. They began farming yams, including their coveted rea, malanga (a root vegetable), and a large variety of vegetables and edible herbs. While they lived in the depths of the Ole, they neither cut their hair nor shaved their beards, taking on savage, frightening appearance.

It happened that porcupines would eat their crops, and, as a consequence, the Batetes were zealous in their extermination. On one occasion, two men named Ebando and Mohiché went out to hunt them. In following their trail, they arrived at the top of the Lopeló mountains. From these heights they could discern a world of new and unknown horizons. They longed to explore the country and, setting off, soon arrived at Oboake, center of the region of the original Batetes. There they found extensive yam plantings, including the rea, malanga, and widespread palm groves. Presenting themselves to the botuku of the place, who received them with kind affability, they lodged for two nights in their rijata or ritaka (public meeting house). Their hosts then sent them off with expressions of great solicitude and caring, providing them with the things necessary for their walk home.

Ebando and Mohiché returned to their own land well pleased. They told their village about what they had seen on the other side of the mountains, painting a vivid picture of luxurious vegetation, fertility, and wealth. They described with what ease they could seize it and leave their deep and dismal valley. Furthermore, they told the others, the residents of the new country were pacifists and might well allow them to live among them. But, should they refuse, they could declare war on them. Hopes began building to conquer them and throw them out of the region.

These Batetes had prodigiously multiplied in the years they lived in the depths of the Grand Caldera. Having unkempt beards and quite long hairstyles, they appeared odd – frightful – like something that comes from beyond the grave.

They left the Ole River and moved up the slopes of the Lopeló. Arriving at the top, they found a huge Batete population of the Batoikoppo, Baloeri, Basapo, Basupú, Banapá, Basilé, and Bariarebola, which is, the people who live in the extensive terrain included between the Ope and Eputu rivers.

(1) Maurice Delafosse (1870-1926) French scholar, teacher, and author of numerous books on African languages, history, and culture, including “Negroes in Africa: History and Culture,” Washington: Associated Publishers, 1931. This paragraph and the next paraphrase that book. --Trans.

(2) Modern thought on Bantu origin and expansion places the cradle of the Bantu languages in Nigeria’s Benue Valley. According to Jan Vansima, in Paths in the Rainforest (University of Wisconsin Press, 1990): “In that general area, the Bantu family split into two branches: eastern and western Bantu, a split dated by glottochronology to c. 3000 BC. Western Bantu evolved east of the Cross River in western Cameroon, both on the then-forested Bamileke Plateau and on the lowlands near the ocean.” Author John Reader, in his book Africa: A Biography of the Continent (Alfred A. Knopf, 1998), also puts Bantu dispersion from their cradle-land at around 5000 years ago. The Bubis still are believed to have been among the first Bantu to migrate, and probably first arrived on Bioko sometime between 2000 and 3000 BC. Vansima notes: “Among the early splits, some were caused by the isolation of small groups moving out of reach. That seems to be the case for the Bioko and the Myene-Tsogo group, who moved by sea. ... Archaeological evidence attests to the early phases of settlement on Bioko. The earliest sites lie on the northern coast. They reveal a Neolithic occupation without ceramics, which has not been dated. From the seventh century AD on, pottery appears.” A second wave of migration from the African coast to Bioko Island accounts for much-later settlements. Vansima writes: “Most traditions tell of a Great Migration comprising four waves of immigrants. ... (Evidence) suggests that the immigrants conquered the earlier Bubi settlers. Nevertheless, the archaeological and linguistic evidence makes it clear that, conquerors or not, the immigrants adopted the language and the material culture of the aboriginal population. ... The archaeological evidence in hand suggests that the Great Migration ended in the fourteenth century.” -- Trans.